The Writer's Tarot™

a Wicked Works Project

The Atomic Story

Atomic Story Approach: Of Science & Magic

Countless volumes of books, college curricula, and even entire careers have been devoted to address the complex topic of story structure and dynamics. They're not wrong, but with regard to this exercise, remember that the more you embrace structural templates and formula, the more limited and imitative will be your results. It's absolutely essential to understand the fundamentals of story structure. But beyond that, do try to listen to that mystical magical inner voice. Therein lies any story worth telling.

The following material assumes you have a basic working knowledge of the English language and grammar. In this regard, a formal education is best. As for story composition, you should at least read a book or two on the subject. But then, browse over the Atomic Story approach. There's no requirement to follow our Atomic philosophy when using The Writer's Tarot™, but isn't it nice to have options? Regardless of preference, at least have a quick read and maybe you'll find something useful in the following passages.

Countless volumes of books, college curricula, and even entire careers have been devoted to address the complex topic of story structure and dynamics. They're not wrong, but with regard to this exercise, remember that the more you embrace structural templates and formula, the more limited and imitative will be your results. It's absolutely essential to understand the fundamentals of story structure. But beyond that, do try to listen to that mystical magical inner voice. Therein lies any story worth telling.

The following material assumes you have a basic working knowledge of the English language and grammar. In this regard, a formal education is best. As for story composition, you should at least read a book or two on the subject. But then, browse over the Atomic Story approach. There's no requirement to follow our Atomic philosophy when using The Writer's Tarot™, but isn't it nice to have options? Regardless of preference, at least have a quick read and maybe you'll find something useful in the following passages.

Introducing the Story Atom:

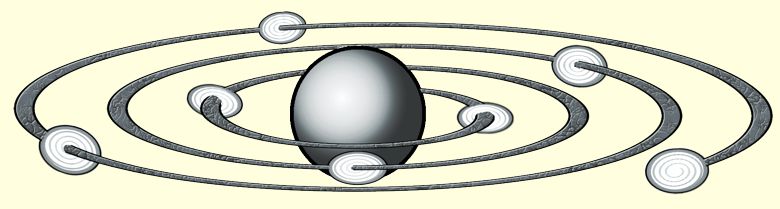

You may have heard the terms “story line” or “plot line” or “story arc” and those are all well and good, but imagine what happens when you let go of the ends of that line or arc and allow a story assume its natural shape. Let’s imagine it coils itself into a kind of spiraling atomic structure, with the story components positioned along a diminishing orbit around what has now become the nucleus of the story, or the heart of it. In this way, you can see how everything revolves around the heart of your story, which we’ll call its core.

You may have heard the terms “story line” or “plot line” or “story arc” and those are all well and good, but imagine what happens when you let go of the ends of that line or arc and allow a story assume its natural shape. Let’s imagine it coils itself into a kind of spiraling atomic structure, with the story components positioned along a diminishing orbit around what has now become the nucleus of the story, or the heart of it. In this way, you can see how everything revolves around the heart of your story, which we’ll call its core.

Story Core:

Here is the heart and soul of it. Essentially, you're providing a short paragraph that explains--in very broad strokes--why your story is worthwhile and how it will endear with the audience. Consider why the tale should be told. Consider the emotional appeal. Is the story meant to amuse, or perhaps to incite action or inspire empathy? Will it educate, entertain, or pursuade? What's the endearing gimmick or punch line or payload?

Don't confuse your story's core with its summary or outline or overview. Those other things tell the "what" of it. But at its core is always the "why". The "why" defines profound aspects of the story that will impact and connect with your reader. And the profound exists on a sliding scale, from "mildly amusing & memorable" to "life-changing". Also, as a rule--and much like the telling of a joke--the longer your story, the more profound or impactful it must be for the audience to consider it worthwhile. Remember that the core/heart of your story is all about how it resonates with the audience.

Story Core can be tricky, so we've provided a few examples below:

Example #1 - from Buddha's Revenge, as presented at Wicked Works Mag:

"Engages/hooks reader with interesting future tech (curiosity/logic), hints of injustice (ethics), and a sympathetic underdog character (empathy). Frightening abuse of this future tech jars reader into pondering potential dangers and giving value to caution (community views/values)."

Example #2 - from The Outsider (H.P. Lovecraft), as presented at Wicked Works Mag:

"Engages/hooks reader with empathy, via confusion and loneliness of central character, also curiosity (logic) about the bizarre world illustrated. Jarring surprise twist introduces a revolting monster, but in sympathetic frame to inspire empathy for those who are different (community views/values)."

Here is the heart and soul of it. Essentially, you're providing a short paragraph that explains--in very broad strokes--why your story is worthwhile and how it will endear with the audience. Consider why the tale should be told. Consider the emotional appeal. Is the story meant to amuse, or perhaps to incite action or inspire empathy? Will it educate, entertain, or pursuade? What's the endearing gimmick or punch line or payload?

Don't confuse your story's core with its summary or outline or overview. Those other things tell the "what" of it. But at its core is always the "why". The "why" defines profound aspects of the story that will impact and connect with your reader. And the profound exists on a sliding scale, from "mildly amusing & memorable" to "life-changing". Also, as a rule--and much like the telling of a joke--the longer your story, the more profound or impactful it must be for the audience to consider it worthwhile. Remember that the core/heart of your story is all about how it resonates with the audience.

Story Core can be tricky, so we've provided a few examples below:

Example #1 - from Buddha's Revenge, as presented at Wicked Works Mag:

"Engages/hooks reader with interesting future tech (curiosity/logic), hints of injustice (ethics), and a sympathetic underdog character (empathy). Frightening abuse of this future tech jars reader into pondering potential dangers and giving value to caution (community views/values)."

Example #2 - from The Outsider (H.P. Lovecraft), as presented at Wicked Works Mag:

"Engages/hooks reader with empathy, via confusion and loneliness of central character, also curiosity (logic) about the bizarre world illustrated. Jarring surprise twist introduces a revolting monster, but in sympathetic frame to inspire empathy for those who are different (community views/values)."

Plot Point:

Those spiraling rings of our story atom track the story’s progress, from beginning (outermost ring) to its core, which is precisely the same path your reader takes. Along that path is a series of fixed plot points, each one addressing one or more plot objectives, each one a key stepping stone along the reader’s path. Interestingly, the plot point can also be seen as an atomic structure in itself, with a series of scene or exposition nodes (all of these addressing plot objectives) arranged in spiraling orbit around its own core of purpose--which, for plot points, will always be a collection of plot objectives. This purpose centers the heart of any plot point precisely along the spiraling path of the story. The first plot point (outer ring) will be a story’s beginning, and the last plot point, before arriving at the core, will be the story’s end.

There are typically a minimum of three plot points. One (or more) will define your story's Prime, used to establish a situational baseline and hook. One (or more) will define a Trigger, where some change or revelation alters/disrupts the baseline. And one (or more) will define an accompanying Result, where a reaction to the Trigger is played out and story baseline is revised. There can also be an optional weave of secondary plotlines, or sub-plots, playing out along the way. Note that we'll describe Prime, Trigger, and Result next, at greater length.

Each plot point is comprised of one or more scenes (and or expositions). You should determine where one plot point ends and the next begins by looking for clean/obvious breaks between plot objectives and their groupings, and by evaluating the state of suspense/anticipation at the end of each scene. As a rule of thumb, consider that a book chapter is usually structured around a single plot point (exceptions where subplots run in parallel). How you divide up your plot points is a largely subjective matter, but each of these should land completely within the Prime or a Trigger or a Result.

Those spiraling rings of our story atom track the story’s progress, from beginning (outermost ring) to its core, which is precisely the same path your reader takes. Along that path is a series of fixed plot points, each one addressing one or more plot objectives, each one a key stepping stone along the reader’s path. Interestingly, the plot point can also be seen as an atomic structure in itself, with a series of scene or exposition nodes (all of these addressing plot objectives) arranged in spiraling orbit around its own core of purpose--which, for plot points, will always be a collection of plot objectives. This purpose centers the heart of any plot point precisely along the spiraling path of the story. The first plot point (outer ring) will be a story’s beginning, and the last plot point, before arriving at the core, will be the story’s end.

There are typically a minimum of three plot points. One (or more) will define your story's Prime, used to establish a situational baseline and hook. One (or more) will define a Trigger, where some change or revelation alters/disrupts the baseline. And one (or more) will define an accompanying Result, where a reaction to the Trigger is played out and story baseline is revised. There can also be an optional weave of secondary plotlines, or sub-plots, playing out along the way. Note that we'll describe Prime, Trigger, and Result next, at greater length.

Each plot point is comprised of one or more scenes (and or expositions). You should determine where one plot point ends and the next begins by looking for clean/obvious breaks between plot objectives and their groupings, and by evaluating the state of suspense/anticipation at the end of each scene. As a rule of thumb, consider that a book chapter is usually structured around a single plot point (exceptions where subplots run in parallel). How you divide up your plot points is a largely subjective matter, but each of these should land completely within the Prime or a Trigger or a Result.

The Prime, Trigger, and Result

In simplest terms, your story is plotted to present a Prime and then one or more Trigger/Result pairings. Here, we'll define those three terms.

Note: Pay particular attention to recurrence of the word profound below. This is an important word. It's a placeholder for anything your reader would deem significant and worthwhile. Profound content is what gives value to your story. For this reason, that same content is also usually referenced in defining the story's Core.

Prime:

Prime represents a situational baseline, plus the hook. Baseline introduces readers to the story world, establishing tone (via narrative voice) and overall sense of that world prior to the story's Trigger (see next). And the hook is some profound element of that world which grabs the readers' attention and engages their intellectual curiosity, morality, or empathy. This element can be a character, community, organization, race or species, technology, philosophy, place, prop, event, etc. Readers may love it or hate it or anything between, but that feeling should be compelling enough to commit them to follow your story.

Trigger:

Trigger is a point at which your story’s baseline is altered in some profound way. This could manifest in the introduction of another character who challenges or conflicts with someone or something from your Prime, or else a conflicting new event or condition, or perhaps nothing more than a subtle change of course and subsequent desire to correct this; or, a discovery which inspires some resulting goal. In any case, it must strum the strings which tie your reader to the Prime (via its hook). Sometimes the initial response to a Trigger is included as part of the Trigger (instantaneous), while other times, it may be delayed sufficiently to appear within the accompanying Result. Or maybe you'll opt to split the response between these two. Response is transitional, so you do have options.

Result:

Result is a profound outcome to your story's Trigger (may also optionally include all or part of the Trigger response). What were the key goals, and were they achieved? Were challenges/conflicts overcome? What are the significant changes? The Result will illustrate a revised situational baseline (relative tone and sense of the world, and any impact on your hook). As with Prime and Trigger, your Result should sufficiently strum those same strings linking your readers from the beginning through to that final resonating chord.

A story can optionally have multiple Trigger/Result pairings. This is how to raise the stakes, much like multiple betting rounds in a game of poker. And it inspires greater reader engagement. But also, just like betting in poker, remember that each additional round must raise the stakes. It's a building process.

Your story is a composition of its Prime plus one or more Trigger/Result pairings, and each of these are defined as a list of plot objectives which, in turn, are grouped into plot points. And those plot points orbit the core of our Atomic Story model.

In simplest terms, your story is plotted to present a Prime and then one or more Trigger/Result pairings. Here, we'll define those three terms.

Note: Pay particular attention to recurrence of the word profound below. This is an important word. It's a placeholder for anything your reader would deem significant and worthwhile. Profound content is what gives value to your story. For this reason, that same content is also usually referenced in defining the story's Core.

Prime:

Prime represents a situational baseline, plus the hook. Baseline introduces readers to the story world, establishing tone (via narrative voice) and overall sense of that world prior to the story's Trigger (see next). And the hook is some profound element of that world which grabs the readers' attention and engages their intellectual curiosity, morality, or empathy. This element can be a character, community, organization, race or species, technology, philosophy, place, prop, event, etc. Readers may love it or hate it or anything between, but that feeling should be compelling enough to commit them to follow your story.

Trigger:

Trigger is a point at which your story’s baseline is altered in some profound way. This could manifest in the introduction of another character who challenges or conflicts with someone or something from your Prime, or else a conflicting new event or condition, or perhaps nothing more than a subtle change of course and subsequent desire to correct this; or, a discovery which inspires some resulting goal. In any case, it must strum the strings which tie your reader to the Prime (via its hook). Sometimes the initial response to a Trigger is included as part of the Trigger (instantaneous), while other times, it may be delayed sufficiently to appear within the accompanying Result. Or maybe you'll opt to split the response between these two. Response is transitional, so you do have options.

Result:

Result is a profound outcome to your story's Trigger (may also optionally include all or part of the Trigger response). What were the key goals, and were they achieved? Were challenges/conflicts overcome? What are the significant changes? The Result will illustrate a revised situational baseline (relative tone and sense of the world, and any impact on your hook). As with Prime and Trigger, your Result should sufficiently strum those same strings linking your readers from the beginning through to that final resonating chord.

A story can optionally have multiple Trigger/Result pairings. This is how to raise the stakes, much like multiple betting rounds in a game of poker. And it inspires greater reader engagement. But also, just like betting in poker, remember that each additional round must raise the stakes. It's a building process.

Your story is a composition of its Prime plus one or more Trigger/Result pairings, and each of these are defined as a list of plot objectives which, in turn, are grouped into plot points. And those plot points orbit the core of our Atomic Story model.

Scene:

Here is where the actual writing occurs!!!

As stated before, plot points are also atomic structures, and at their heart is always intent to progress the story via plot point objectives. The one or more nodes found orbiting the core of a plot point atom are Scene nodes/atoms. Each scene includes a variety of components interacting to produce a desired result (plot objectives). Narrative voice, characters, setting, props, dialogue, events, actions, and exposition are components or nodes of the scene, and we’ll explore those next.

Here is where the actual writing occurs!!!

As stated before, plot points are also atomic structures, and at their heart is always intent to progress the story via plot point objectives. The one or more nodes found orbiting the core of a plot point atom are Scene nodes/atoms. Each scene includes a variety of components interacting to produce a desired result (plot objectives). Narrative voice, characters, setting, props, dialogue, events, actions, and exposition are components or nodes of the scene, and we’ll explore those next.

Scene Components >> Narrative Voice:

Before writing a scene, you must choose a narrative voice and then stick with it throughout that scene (if not the entire story). There are many nuances, but the fundamentals are some combination of these three components: point of view (POV), tense, and tone. We'll describe those next.

Before writing a scene, you must choose a narrative voice and then stick with it throughout that scene (if not the entire story). There are many nuances, but the fundamentals are some combination of these three components: point of view (POV), tense, and tone. We'll describe those next.

- Narrative Point of View (POV) -

POV determines where your reader is positioned to witness a scene.

You can put the reader inside the mind of a single character, revealing your scene through the senses, thoughts, biases, and actions of that character. Or you can perch the reader over his/her/its shoulder, so both would perceive the world similarly, except the reader has no access to the other's thoughts or inner workings. Or your reader may free-float about the scene like some invisible ghost, untethered and unhindered by the limitations of any character; but also, with no access to their thoughts. Lastly, there is the omniscient "god's eye" perspective, which can move anywhere in a scene and also witness the thoughts of all characters. Consider what information must be conveyed to your reader and also what information should be withheld, and this will best indicate where to position your POV.

Note: Removing your reader from the scene altogether (informing without a scene) results in exposition, which we'll address later.

When a POV character is selected, you must then establish the reader's relationship with that character--how the two will interact. This can be the more intimate 1st person (I, me, we) primary (main character) or peripheral (not the main character in the scene), where POV character informs reader directly. Or, on rare occasions it may be 2nd person (you), which results in a kind of role reversal where the reader is assigned the role of a character in the story. Or lastly, it can be one of the 3rd person (he/she/they/it) perspectives, including limited (narrator knows only what POV character knows), multiple (narrator can follow multiple characters), or omniscient ("god's eye", narrator knows everything).

Remember to choose with care, because one of these POVs and consequent character perspectives will be best suited for illustrating your scene or story.

You can put the reader inside the mind of a single character, revealing your scene through the senses, thoughts, biases, and actions of that character. Or you can perch the reader over his/her/its shoulder, so both would perceive the world similarly, except the reader has no access to the other's thoughts or inner workings. Or your reader may free-float about the scene like some invisible ghost, untethered and unhindered by the limitations of any character; but also, with no access to their thoughts. Lastly, there is the omniscient "god's eye" perspective, which can move anywhere in a scene and also witness the thoughts of all characters. Consider what information must be conveyed to your reader and also what information should be withheld, and this will best indicate where to position your POV.

Note: Removing your reader from the scene altogether (informing without a scene) results in exposition, which we'll address later.

When a POV character is selected, you must then establish the reader's relationship with that character--how the two will interact. This can be the more intimate 1st person (I, me, we) primary (main character) or peripheral (not the main character in the scene), where POV character informs reader directly. Or, on rare occasions it may be 2nd person (you), which results in a kind of role reversal where the reader is assigned the role of a character in the story. Or lastly, it can be one of the 3rd person (he/she/they/it) perspectives, including limited (narrator knows only what POV character knows), multiple (narrator can follow multiple characters), or omniscient ("god's eye", narrator knows everything).

Remember to choose with care, because one of these POVs and consequent character perspectives will be best suited for illustrating your scene or story.

- Narrative Tense -

This simply indicates the narrative is recounting events which already occurred (past tense), or as they happen (present tense), or on rare occasion, events which will come to pass (future or prophetic tense). Mixed tenses are a common mistake for beginning writers, so remember to pick a tense and stick with it.

- Narrative Tone -

The third and final aspect of narrative voice refers to a story’s attitude or mood or emotional expression. This can change to mirror the dramas playing out along the way. It’s seen in writing syntax, POV, diction, and level of formality. Note that POV—which is often subjective or biased—has a heavy influence over tone.

All of these elements—POV, tense, and tone—combine to provide a story’s narrative voice. Again, these should not be random selections: seek the most effective combination for any scene.

All of these elements—POV, tense, and tone—combine to provide a story’s narrative voice. Again, these should not be random selections: seek the most effective combination for any scene.

Scene Components >> Character:

Characters are any cognitive entities interacting with your story in some way which progresses its plot. They may or may not be human, but remember that your reader is human, and so must relate to them in some human way. For example, you can read a book about a pack of wild wolves and find yourself relating to their struggle for food and shelter or family bonds in a very human way. We humanize all sorts of things, including inanimate objects such as toys or cars, or our pets, and we even humanize our gods. Consider this when writing non-human characters.

Characters are considered the most complex and evolving components in storytelling. Unfortunately, there’s no time here in our Writers’ Tarot guide to sufficiently address all the related nodes (yes, the character is also an atomic structure, and its core purpose is also to serve the plot progression). But you’ll get the general idea, enough so that the rest should come to you with minimal effort.

Now, let’s imagine writing a character as a kind of mathematic equation: the sum of all traits defining his/her/its origin, plus any traits picked up along the timeline of that character’s life. And also, because you are the writer and know the character’s destiny, it’s possible to include traits presently unknown to the character or reader--hidden or future traits. By “traits” we mean any assignable quality or condition or experience which helps us to qualify and quantify a character for dynamic interaction with other characters or elements in our story. This is how we determine the character’s behavior and actions and outcome in any given scene--the whole point of the exercise. A sum of his/her/its traits dictates how a character should respond or behave.

Examples of character traits include (but are far from limited to) the following: name, ethnicity, age, sex, skin color, eye color, hair color, hair style, birthmarks, tattoos, scars, place of residence, possessions, general health, specific maladies, educational background, vocation and current employer, social status, wealth, profound childhood/historic events, psychological quirks or phobias, common expressions, typical attire, political standing, owned transport, family tree members, IQ, height, weight, hobbies, religious preference, spells known, etc., etc.

Everything is relative. When developing a character, it’s not necessary to define every possible trait that character has. As a writer, your goal is much simpler: ONLY define those traits which will be helpful—in some specific way—for telling your story. Just focus on what is needed for scene interaction. What similar or contrasting traits between your characters may impact their relationships? What traits apply to their interaction with a scene and plotline? What traits compel or else impede them in some particular direction? And finally, what traits will make them provocative in a memorable way for your reader (e.g. sympathetic hero? detestable villain? intriguing mentor? etc.)?

A “starter” list of character traits is included on the Supplementals page. Feel free to expand on that list as you wish. But also, remember to address only those traits relative to your story.

Characters are any cognitive entities interacting with your story in some way which progresses its plot. They may or may not be human, but remember that your reader is human, and so must relate to them in some human way. For example, you can read a book about a pack of wild wolves and find yourself relating to their struggle for food and shelter or family bonds in a very human way. We humanize all sorts of things, including inanimate objects such as toys or cars, or our pets, and we even humanize our gods. Consider this when writing non-human characters.

Characters are considered the most complex and evolving components in storytelling. Unfortunately, there’s no time here in our Writers’ Tarot guide to sufficiently address all the related nodes (yes, the character is also an atomic structure, and its core purpose is also to serve the plot progression). But you’ll get the general idea, enough so that the rest should come to you with minimal effort.

Now, let’s imagine writing a character as a kind of mathematic equation: the sum of all traits defining his/her/its origin, plus any traits picked up along the timeline of that character’s life. And also, because you are the writer and know the character’s destiny, it’s possible to include traits presently unknown to the character or reader--hidden or future traits. By “traits” we mean any assignable quality or condition or experience which helps us to qualify and quantify a character for dynamic interaction with other characters or elements in our story. This is how we determine the character’s behavior and actions and outcome in any given scene--the whole point of the exercise. A sum of his/her/its traits dictates how a character should respond or behave.

Examples of character traits include (but are far from limited to) the following: name, ethnicity, age, sex, skin color, eye color, hair color, hair style, birthmarks, tattoos, scars, place of residence, possessions, general health, specific maladies, educational background, vocation and current employer, social status, wealth, profound childhood/historic events, psychological quirks or phobias, common expressions, typical attire, political standing, owned transport, family tree members, IQ, height, weight, hobbies, religious preference, spells known, etc., etc.

Everything is relative. When developing a character, it’s not necessary to define every possible trait that character has. As a writer, your goal is much simpler: ONLY define those traits which will be helpful—in some specific way—for telling your story. Just focus on what is needed for scene interaction. What similar or contrasting traits between your characters may impact their relationships? What traits apply to their interaction with a scene and plotline? What traits compel or else impede them in some particular direction? And finally, what traits will make them provocative in a memorable way for your reader (e.g. sympathetic hero? detestable villain? intriguing mentor? etc.)?

A “starter” list of character traits is included on the Supplementals page. Feel free to expand on that list as you wish. But also, remember to address only those traits relative to your story.

Scene Components >> Setting:

This is the stage upon which a scene plays out. There are many factors to consider with setting, such as location, climate, season, terrain, background events, cultural references, indigenous animals or insects, time of day, background actors, props, sensory input, and on and on.

This is the stage upon which a scene plays out. There are many factors to consider with setting, such as location, climate, season, terrain, background events, cultural references, indigenous animals or insects, time of day, background actors, props, sensory input, and on and on.

Scene Components >> Prop:

A prop is anything characters interact with in a scene, such as the murder weapon, or a curious bumper sticker, or sunglasses, or an antiquated issue of Time Magazine on the coffee table at a dentist’s office, etc. As a writer, you should always consider the power of props to help illustrate more dynamic and colorful scenes, as well as to advance your plot. Also, it’s important to always keep track of your props in a scene and throughout the story--their specific locations and conditions.

A prop is anything characters interact with in a scene, such as the murder weapon, or a curious bumper sticker, or sunglasses, or an antiquated issue of Time Magazine on the coffee table at a dentist’s office, etc. As a writer, you should always consider the power of props to help illustrate more dynamic and colorful scenes, as well as to advance your plot. Also, it’s important to always keep track of your props in a scene and throughout the story--their specific locations and conditions.

Scene Components >> Dialogue:

An entire story can be told through dialogue, the verbal exchange between two or more characters. When done well, the need for reference tags like “James said” or “Jesse screamed” is minimal or even non-existent, because readers can identify your characters by the words they speak. Consider a character’s social and educational background, current mental state, knowledge of the subject matter addressed, dialect or accent, and any oral quirks (such as a stutter or repeated expression, etc.) when writing dialogue. Their speech should reflect your characters’ personalities.

Additionally, you should remember that any dialogue appearing in your story must serve a specific purpose. For example, it’s an excellent way to get important information to your reader, as when a doctor explains the severity of an injury to another character (and the reader), which informs and also stresses urgency in your story. Or, a little dialogue can reveal important personality traits, important to plot or for character illustration. But if the best justification you have for any dialogue is that it’s clever or funny, then there’s a very good chance it should be cut. Dialogue often goes nowhere in real life, but don't let that happen with your story.

Note: The above applies to monologue (verbal expression of single character) as well.

An entire story can be told through dialogue, the verbal exchange between two or more characters. When done well, the need for reference tags like “James said” or “Jesse screamed” is minimal or even non-existent, because readers can identify your characters by the words they speak. Consider a character’s social and educational background, current mental state, knowledge of the subject matter addressed, dialect or accent, and any oral quirks (such as a stutter or repeated expression, etc.) when writing dialogue. Their speech should reflect your characters’ personalities.

Additionally, you should remember that any dialogue appearing in your story must serve a specific purpose. For example, it’s an excellent way to get important information to your reader, as when a doctor explains the severity of an injury to another character (and the reader), which informs and also stresses urgency in your story. Or, a little dialogue can reveal important personality traits, important to plot or for character illustration. But if the best justification you have for any dialogue is that it’s clever or funny, then there’s a very good chance it should be cut. Dialogue often goes nowhere in real life, but don't let that happen with your story.

Note: The above applies to monologue (verbal expression of single character) as well.

Scene Components >> Event:

If Setting is the stage, then Event is what plays out on that stage. Scenes typically include key events (instrumental in progressing scene, plot, and story) and background events (part of the setting). These can be “Incidents” straight from the Writer's Tarot™, or dialogues, or physical or mental activities, or social activities or acts of nature, etc., etc. How a scene gets from start to finish is illustrated through its events.

If Setting is the stage, then Event is what plays out on that stage. Scenes typically include key events (instrumental in progressing scene, plot, and story) and background events (part of the setting). These can be “Incidents” straight from the Writer's Tarot™, or dialogues, or physical or mental activities, or social activities or acts of nature, etc., etc. How a scene gets from start to finish is illustrated through its events.

Scene Components >> Action:

Events are a broad overview of how a scene changes or progresses, while actions are a subset of this and refer to each individual step along the way. For example, a domestic squabble would be an event, while one character shouting “I hate you!” or throwing a plate or slamming a door would all be actions within that event, each one helping move the event along--and by consequence, the scene and story--toward a conclusion. And as with events, some actions are just part of the background, to help illustrate a scene’s setting. In our atomic infrastructure, actions would appear as nodes orbiting around event atoms.

Events are a broad overview of how a scene changes or progresses, while actions are a subset of this and refer to each individual step along the way. For example, a domestic squabble would be an event, while one character shouting “I hate you!” or throwing a plate or slamming a door would all be actions within that event, each one helping move the event along--and by consequence, the scene and story--toward a conclusion. And as with events, some actions are just part of the background, to help illustrate a scene’s setting. In our atomic infrastructure, actions would appear as nodes orbiting around event atoms.

Scene Components >> Exposition:

This is the dissemination of important information to your reader in a method occurring mostly outside the scope of a scene’s natural dynamics. Some refer to this as a “data dump” because that’s how it often feels to the reader (which is bad).

Exposition can take place inside a scene as part of the narrative, or else as a standalone story node--a rare alternative to the scene. You’ll often find an exposition node at the preface to epic fantasy, Sci-Fi, or historical fiction, where the author provides some background for the story world. Exposition is considered a “passive” writing style and generally discouraged in fiction. It’s a good idea to keep the old “Show it: don’t tell it” adage in mind.

This is the dissemination of important information to your reader in a method occurring mostly outside the scope of a scene’s natural dynamics. Some refer to this as a “data dump” because that’s how it often feels to the reader (which is bad).

Exposition can take place inside a scene as part of the narrative, or else as a standalone story node--a rare alternative to the scene. You’ll often find an exposition node at the preface to epic fantasy, Sci-Fi, or historical fiction, where the author provides some background for the story world. Exposition is considered a “passive” writing style and generally discouraged in fiction. It’s a good idea to keep the old “Show it: don’t tell it” adage in mind.

Summary:

So now, we’ve touched on the elements of our Atomic Story and seen how everything revolves around the heart or “Core” of it. Before that, we discussed the composition of the Writer's Tarot™ deck. Next, we’ll provide some card reading basics, then bring it all together by exploring various “reading” samples which will help you build your stories and astound your readers.

So now, we’ve touched on the elements of our Atomic Story and seen how everything revolves around the heart or “Core” of it. Before that, we discussed the composition of the Writer's Tarot™ deck. Next, we’ll provide some card reading basics, then bring it all together by exploring various “reading” samples which will help you build your stories and astound your readers.